This is Unit 8 from the September 11th Personal Stories of Transformation toolkit. Jim and Gordon lost their brothers, one in the attack on the Pentagon and one on Flight 93. Each took leadership roles in building memorials that pay tribute to the attacks on the nation and the lives lost.The full classroom resource kit contains 8 videos. Each story is accompanied by discussion questions that guide students to connect outcomes of the historic events of September 11th to the choices they make in their own lives. These materials are provided courtesy of The Tribute WTC Visitor Center.

These classroom resources provide historic context, research links, and community service projects for each story. Every year, the September 11 Memorial & Museum puts together a video that can be used in the classroom to start a discussion on this difficult topic. In this year's video, available on-demand on September 10, the daughter of a pilot killed in one of the planes that crashed into the World Trade Center tells her story. We also hear from a student who attended the Florida elementary school where President George W. Bush was first told about the 9/11 attacks. The program will be interpreted in American Sign Language, captioned, and can be played with Spanish subtitles. You can sign your class up for an interactive live chat where students can pose questions to museum staff.

Follow these guidelines for talking with young people about terrorism in the classroom. This is Unit 5 from the September 11th Personal Stories of Transformation toolkit. Susan Retik is a widow from Boston who lost her husband on American Airlines Flight 11. She and another September 11th widow started an organization to aid widows in Afghanistan.

This is Unit 6 from the September 11th Personal Stories of Transformation toolkit.After September 11th, many Arab, South Asian and Muslim communities in America felt under attack. This is Unit 7 from the September 11th Personal Stories of Transformation toolkit. Tsugio Ito lost his brother in the bombing of Hiroshima and his son on 9/11 at the World Trade Center.

Masahiro Sasaki donated one of the origami cranes folded in 1955 by his sister, the legendary Sadako, to the Tribute WTC Visitor Center as a wish for global peace. In today's classroom, there are myriad challenges to addressing and teaching about the attacks of September 11, their place in history, and their continuing impact on our world. Some of those challenges lie with the adults, the educators — and your own knowledge, memories, experiences, and perspectives on what happened and why. Then there's the challenge of when and how to address it with your class and whether it's a part of the curriculum you teach or not.

And, of course, at this point, no student in a middle school or high school classroom would even have been alive when the attacks took place. For students today, the attacks themselves are truly—and maybe simply—a terrible event of history. The Tribute WTC Visitor Center classroom resources provide historic context, research links, and community service projects for each story.

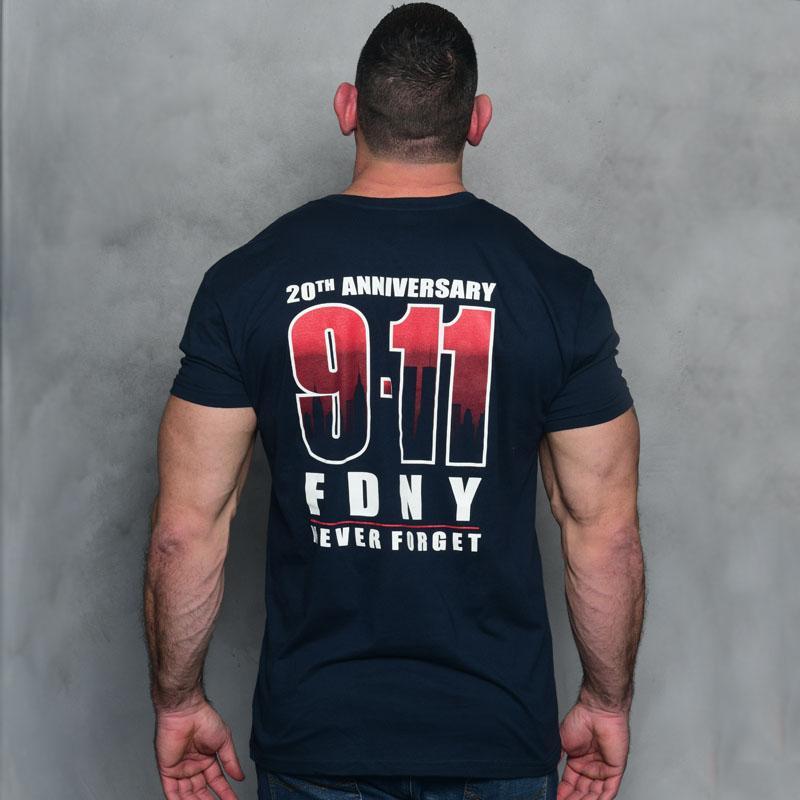

Teaching the events and aftermath of the 20th anniversary of 9/11 can be challenging because of the complex emotions it stirs up in both teacher and student and the sheer size of the topic. Keeping this in mind, we have provided a one-page background text for middle and high school students and a short list of resources for the classroom. Within the resource collections you will find articles, videos, lesson plans, interactive timelines, photo slideshows and other rich content to choose from to meet the needs of your own classroom. But the painful legacy of these events and how they've shaped the world are evident every day.

And young people want to understand more about September 11—not only the events of the day itself, but all that came before and has come after to form the world they live in. Below is a list of resources that can offer you multiple ways to contextualize and teach about what the 20th anniversary of September 11 means. In the days after 9/11, people in New York City came together to console and support each other during this difficult time. They set up impromptu memorials to remember the victims, including some that called for peace and no war. People from other parts of the country, including children and young people, sent cards and gifts, and some came to the city to help out.

At the same time, though, some people were threatened and even attacked because other people thought they looked like those who were behind the attacks. Political leaders, including then President George W. Bush, cautioned that 9/11 should not be an excuse for discriminating against anybody. The site where the buildings came down has been known as Ground Zero ever since. It has become a place for people to go and honor and remember those who were killed that day. Most kids didn't fully understand what was going on or the gravity of the situation, but we were worried because we had never seen our teachers this worried. Later in the day, my English language arts teacher had us journal our feelings and then share.

By social studies that afternoon, I remember my teacher pulling out the map and showing us where Afghanistan was. I remember my math teacher trying to teach us math, but nobody was paying attention, and eventually, he gave up and put the news back on. In band and PE, we had the option to participate in the normal day if we wanted some normalcy, or we could sit out if we wanted. This lesson plan emphasizes the sequence of events that occurred before, during and after 9/11 to help increase students' basic knowledge while correcting inaccuracies and misunderstandings.

Please visit their website for additional information and resources. Looking for more ways to help your students understand the terror attacks and their impact? Use these 9/11 activities and lesson plans in your middle and high school classrooms. Review the videos, photographs, and other resources before sharing them with students as the events depicted are disturbing. This year marks the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

On September 11, 2001, nearly 3,000 people were killed in a series of attacks in the United States. Two hijacked airplanes flew into the World Trade Center in New York, causing the towers to collapse later in the day. Another flew into the Pentagon (U.S. military headquarters) in Arlington, Virginia. Capitol or the White House, crashed into a field in Pennsylvania after passengers and crew attempted to overtake the terrorists. The attacks were carried out by the militant group al-Qaeda. The results say teachers reported not having enough educational materials or resources to add the topic to curriculum plans.

Some said they were concerned about how students or parents may react to lessons on the events — two Hingham families opted out of reading "The Red Bandanna" this year, Goldman said. Several teachers said a general lack of background knowledge of students, as well as student misinformation or belief in conspiracy theories about 9/11, make adding it to lesson plans more complicated. People throughout the United States were shocked by these attacks on American soil. They came together, asking how this could have happened and what it meant. It was a difficult time for Muslims and Arab-Americans, because the men who carried out the attacks were Arabs and Muslims who said they were waging a holy war against the United States.

As a result, some Americans took out their anger on Muslims and Arab-Americans who had had nothing to do with the attacks. Some children were teased or harassed in school; Muslims and Arab-Americans were threatened; in Texas three Muslims were killed. Have students watch poet Glenis Redmond teach a class on how to write a poem. Redmond teaches students how to write a self-portrait poem using alliteration, assonance, and anaphora.

Tell students that the poems they write will not be about themselves. Instead, they will write a self-portrait poem from the perspective of someone who was impacted by 9/11. The subject of their poem can be a person they read about in a book, a news article, or a first-person video account. The person might be a first responder, an eyewitness, a victim of the attacks, or someone who lost a loved one that day. To write the poem, they'll have to gather as much information as possible about the person's experience on 9/11. Allow time for students to share their poems with the class.

Most adults remember clearly the morning of September 11, 2001. Here are five thoughtful novels that will give middle and high school students a sense of what it was like to live through that time in history. The links below lead to novel excerpts, discussion starters, and teachers' guides featuring cross-curricular activities. Middle school teachers very quickly are able to decipher kids running in the hallway.

I heard an "oh my God," at which point I walked quickly to look out into the hallway. One of my teacher teammates was approaching the room as I was opening the door. She had a startled look on her face and asked if I was watching TV.

When I turned it on, we were immediately heartbroken for the people that were on the plane as well as those in the building that was just hit. That only lasted for a minute as the news camera focused on the burning building caught a glimpse of a second plane hitting the second tower. Immediately we knew our country was under attack, and we were sitting in the middle of a military town. A number of my students' parents were living in the neighborhood solely because they were enlisted in the military. Thirteen years ago on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, members of the Islamic extremist group al-Qaeda hijacked four planes in a coordinated terrorist attack.

Two planes crashed into the Twin Towers in downtown New York City, a third plane flew into the Pentagon building in Washington, D.C., and the final plane was brought down by passengers, who had become aware of the other attacks, in a field in Pennsylvania. 2,977 people died in the attacks, including civilians, military personnel in the Pentagon and the emergency fire fighters, police and medical workers who arrived at the scene. I'm going to take us right here to this tree where there in shade and there is sun, so you could have which ever you prefer. So we don't get in everyone's way, if we can stay over here on the left hand side, we'll be in good shape. The memorial is designed for you to make physical contact with it, to actually touch the names. So do not feel that the appropriate behavior that shows respect is to be standoffish.

The only thing that we do ask — and I really doubt that any of you would have the impulse to do this anyhow — do not put things on the name. The other thing I want to say to you is this was truly — you're an international group of people — this was the World Trade Center. They were Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, atheists. Some made their way in the world washing dishes, others ran powerful companies, but almost every single one of them dies that morning because they do something that all of us do with most of our lives — they woke up and they went to work. The south pool stands in the footprint of the South Tower, World Trade Center number two. So that's exactly where World Trade Center number two stood.

Can everyone see that line of trees that goes around the pool? That line of trees represents the outer wall of the building. So that means in a few minutes when we go up to see the falls and you go past those trees, you will be standing in what was once the lobby of World Trade Center number two.

The falls come out in individual rivulets, one for each person killed on 9/11. In the center of the pool, another opening goes on another 10 feet or so. No matter how hard you try, you can't see the bottom of that opening because it's a void, and the void is a symbol of the emptiness that we feel here over the loss of life. What someone will do, visiting a loved one — and please feel free to do the very, very same — take their hand, put it in the water, rub their hand over a name. For example, people who worked in the same office in this building, they're together.

People together in death just the way they were together in life. The only place you'll find them is if you should go into the museum, there's a special part that deals with Al Qaeda. Waisgerber said it can be particularly challenging to teach a topic that students have no memory of — today's high school students weren't yet born — but that teachers and parents have fresh in their minds. He said he encourages teachers to bring personal memories into lesson plans about such an emotional event for so many. I was a new teacher at the school and was so unaware of the events that were taking place just blocks away. When we arrived at the art room, the class of older children was buzzing with a nervous energy, and the teacher had a look of shock on her face as she lowered the window shades.

The fifth-floor room had a direct view of the towers, and the students were witnessing people jumping out of windows. The world was still largely without smartphones or social media. Teachers and students watched the news on boxy TVs strapped to rolling carts that moved between classrooms. Then, one by one, students were called out of class as parents arrived early to bring them home. If the goal of teaching history is to develop citizens who use knowledge of the past to understand the present and inform future decisions, educators need to help students learn from 9/11 and the war on terror, and not just about them. This means going beyond the facts of the day and the collective memory aspects to also engage in inquiry into why they happened and how the U.S. and other nations reacted.

The surveyed teachers view 9/11 as significant – and believe that teaching it honors the goal to never forget. However, they described the challenge of making time for discussing these events when the standards for their class do not necessarily include them, or include 9/11-related topics only at the end of the school year. As a result, the lessons are often limited to one class session on or near the anniversary. It is also taught out of historical context given that the anniversary arrives at the beginning of the school year and most U.S. history courses start in either the 1400s or the post-U.S. These lessons were piloted in over 60 New Jersey school districts, and revised by curriculum developers.

In this lesson, students will read accounts of 9/11 from a firefighter's point of view and then will examine 9/11 through the eyes of other emergency personnel, including firefighters, police officers and other uniformed individuals. This lesson is provided by the 9/11 National Day of Service and a partnership between My Good Deed and the 4 Action Initiative. These lesson plans and activities focus on the 'everyday heroes'—people who worked at the Pentagon and helped with the rescue operations, those involved as first responders, and the individuals who lost their lives as a result of the attack.

These materials best complement the documentary from 45 minutes, 19 seconds through 53 minutes, 39 seconds. For the most comprehensive understanding of the National 9/11 Pentagon Memorial and those affected by the attack, view the documentary from 34 minutes, 59 seconds through 53 minutes, 39 seconds. Photographs can be a powerful and accessible way for students to learn more about what happened on and after Sept. 11. Your support can help us inspire thousands more students and educators with this important history through personal stories, guided tours, powerful lesson plans, and more. Jeremy Stoddard, a professor of the University of Wisconsin's secondary education program, conducted a national survey of more than 1,000 teachers nationwide and asked about how the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks are taught in class.

Results, released in 2019, showed that the events of 9/11 are "included unevenly across states in the U.S. and treated rather superficially in many commonly used textbooks." Accompanying digital materials created by Discovery Education's expert curriculum and content designers help educators integrate the virtual experience into any lesson plan. Included in the resources is a collaborative activity encouraging civic engagement and self-reflection that demonstrates for students how to map out good deed goals. The partnership is also adding to the 9/11 Day collection of lesson plans that help students unlock the power a good deed can have to shape a better tomorrow. Developed for students born after September 11, 2001, this experience highlights ways people in the United States came together during and after the terrorist attacks. During this event, students will meet Jenna Bush Hager, co-host of NBC's Today with Hoda & Jenna, in a town-hall-style session at the 9/11 Tribute Museum.

Students will hear from their peers about the power of good deeds, as well as from other leaders. Direct your students to choose one to listen to and prepare a summary of their experiences and the impact of September 11, 2001 on the individual's life. Provide each student an opportunity to share with the class who they listened to, what they learned, and how the chosen oral history relates to the stories presented in the video clips. We at your National Museum of American History pledge that none of us shall forget that day. As we approach the 20th anniversary of September 11, the museum is committed to working with a wide range of communities to actively expand the stories and experiences of Americans in a post-September 11 world.

We invite you to join us in our work to gather, preserve, and share the many accounts of the ways our world has changed since the September 11 attacks, so that we may collectively contextualize and understand a world forever altered by these tragic events. It was then 33 years later that in real time, from my mother's sister's house in Rhode Island, we experienced September 11, 2001. At the beginning of a school year, and whenever you introduce a potentially controversial and emotional topic, it's appropriate to establish "community agreements"- guidelines for creating a safe space for sharing opinions and feelings. You may have students in your class who have been deeply affected by 9/11. These students may need special support before and after the anniversary observances. Before doing a lesson on 9/11, you may want to tell your students that anyone who fits into the above categories – or is sensitive about the topic for any reason – should feel free to talk with you privately.